In spring 1983, the Museo Rufino Tamayo, an emerging cultural institution in Mexico City at the time, contacted the Barragán + Ferrera office about mounting an exhibition devoted to Barragán’s lifework. The ensuing retrospective at the Museo Rufino Tamayo was the first comprehensive presentation of the architect’s work in his home country. This honour came in the wake of the international recognition brought by the award of the Pritzker Prize in 1980.

During this late period, the Barragán + Ferrera office was in a phase of reorganization as Barragán progressively withdrew from the practice’s activities, while Raúl Ferrera took on greater responsibility for the design process as well as the management of office communications and public relations.

Preparations for the exhibition started in July 1983. The pre-selection of materials to be displayed soon became a substantial project in itself, as drawings, sketches, photographs, publications and other documents from the office were systematically examined and categorized. This demanding task required the full-time commitment of nine people, including Barragán + Ferrera employees and external collaborators. The fluid boundary between studio and home allowed Barragán, in spite of his poor health, to participate. Beyond its inestimable value for the upcoming exhibition, this inventory work laid the foundation for the archival research later undertaken by the Barragan Foundation.

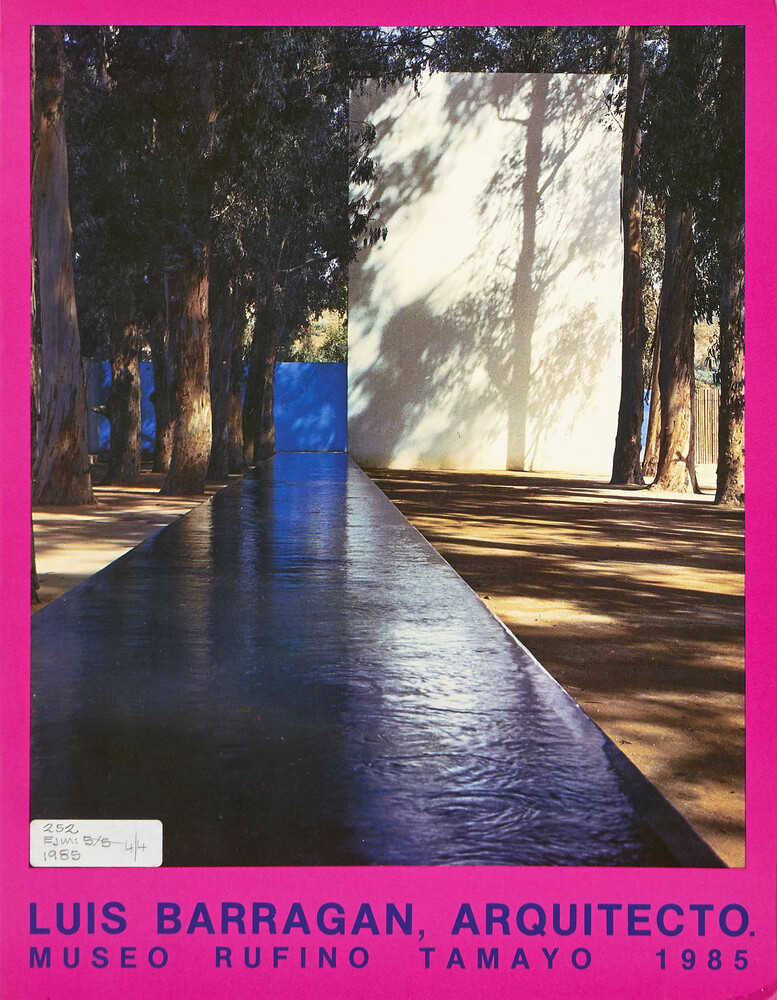

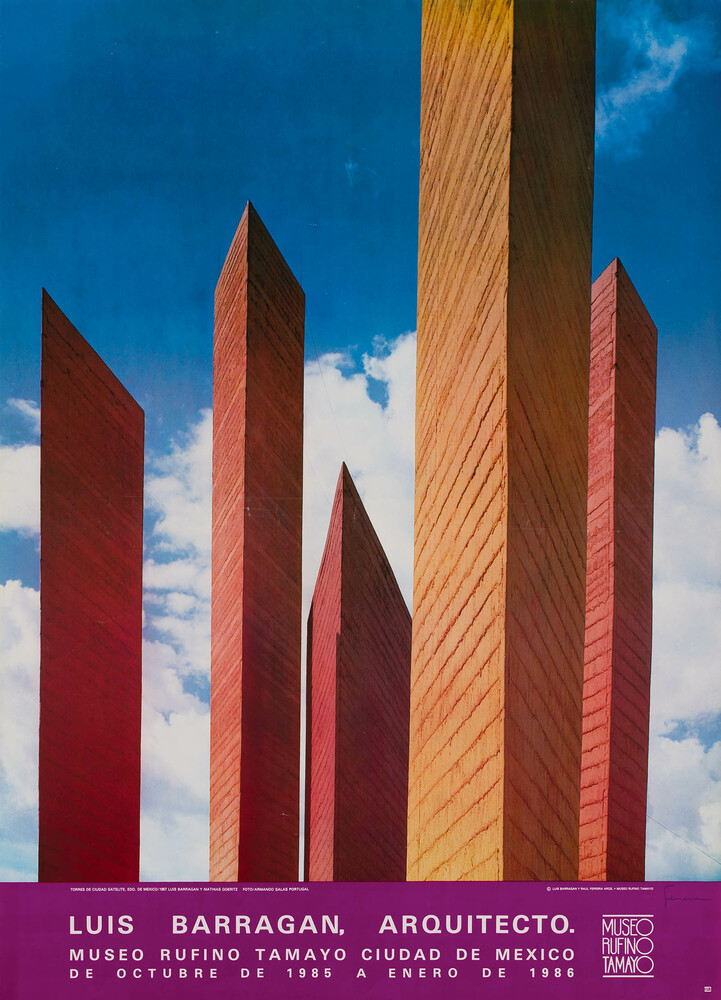

The contract between Barragán + Ferrera and the museum was signed in February 1985. The first proposals for the exhibition layout and design were ready by June. The catalogue publication and publicity efforts for the show were discussed in early July 1985. After Mexico City was hit by a violent earthquake with devastating consequences on 19 September, the scheduled opening on 16 October 1985 had to be postponed. Nevertheless, the exhibition Luis Barragán: Arquitecto opened its doors with just a slight delay on 29 October. Barragán and Ferrera attended the vernissage surrounded by close friends and prominent personalities from the Mexican cultural scene. The opening was Barragán’s last public appearance.

The exhibition presented more than 300 archival documents, including materials from recent projects. The various works were grouped according to aesthetic criteria, with the goal of making the show accessible to a general audience. The ground floor of the museum was dedicated to Barragán’s oeuvre from the 1920s to the 1970s, while the upper floor featured a selection of projects by Barragán + Ferrera. The exhibition opened with a section devoted to the Capuchin Convent Chapel, followed by an area portraying the Lomas Verdes urban development. Only these two works claimed their own space; the other projects were organized on the basis of their typological and aesthetic affinities. Large-scale photographs, mostly by Armando Salas Portugal, evoked the vivid colours, atmospheric ambience and majestic proportions of Barragán’s architecture.

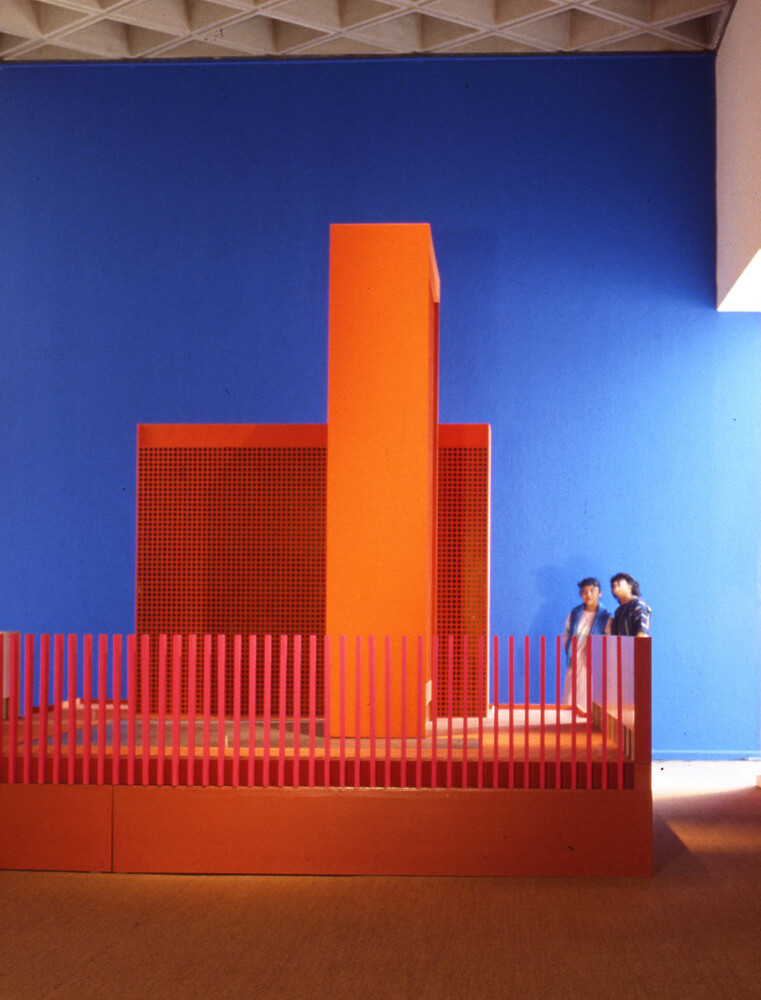

Large models and mock-ups were produced to visualize some unrealized designs, most of them related to urban planning, an often overlooked facet of Barragán’s work. The style and size of these colourful three-dimensional representations echoed architectural tropes of the time, like those seen at the 1980 Venice Architecture Biennale’s La Strada Novissima.

The show was supplemented with original furnishings and artefacts from the Barragán House, such as a selection of ceramic ollas (pots). Taking advantage of the museum hall’s imposing height, two carousel horses were mounted on tall poles, replicating the decorations conceived for equestrian events at Las Arboledas decades earlier. These references lent a semblance of authenticity and sense of place to the exhibits, while also engaging with the museum’s interior.

The accompanying publication comprised two small volumes: the first dedicated to the exhibition itself, the second containing a selection of previously published essays and articles, mostly from the 1970s and early 1980s. The show succeeded in celebrating Barragán’s distinctive career and revealing the architect’s rich legacy to his home country, yet failed to achieve its secondary goal of bringing in new commissions for the office. Despite the considerable effort that went into portraying recent projects, critiques and reviews of the exhibition concentrated on Barragán’s earlier, seminal works and their iconic status. Indeed, the last years of the Barragán + Ferrera partnership were marked by financial struggles as many of its final projects faltered.