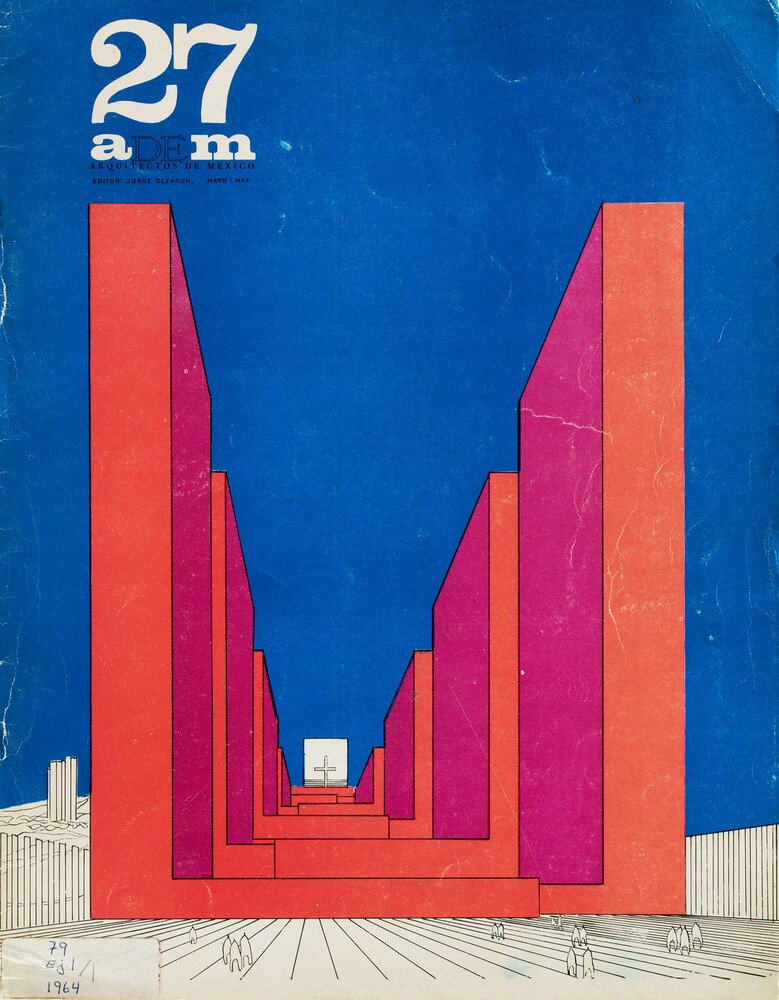

In 1964, Luis Barragán and Juan Sordo Madaleno were commissioned to develop a master plan for a new town with a projected population of 100,000 in an area of 380 hectares on the outskirts of Mexico City. The master plan was completed in 1967, yet the ensuing development, parts of which still exist today, did not fully adhere to the original design. The project was published in the Mexican magazine Arquitectos de México in 1967, and was also featured in the Barragán Retrospective held at the Museo Rufino Tamayo in 1985.

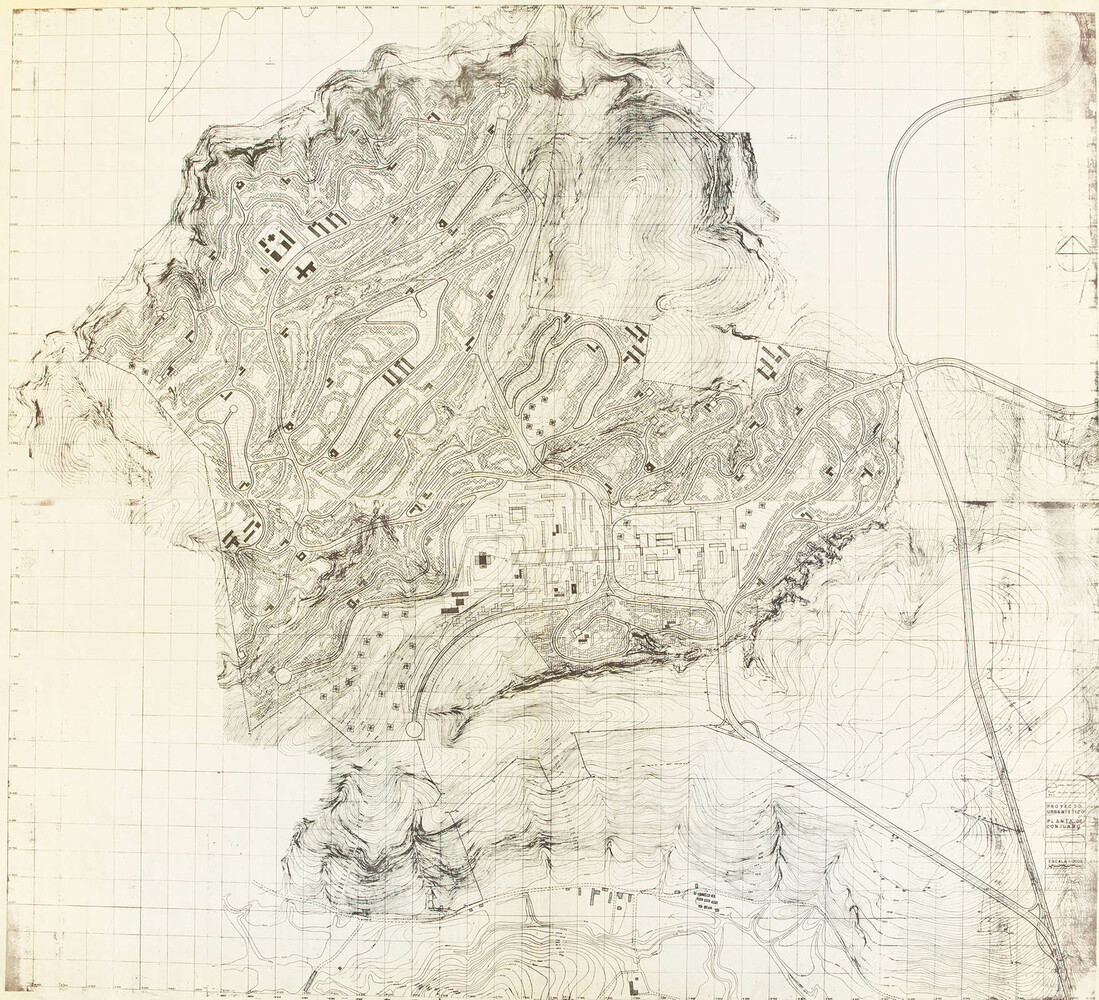

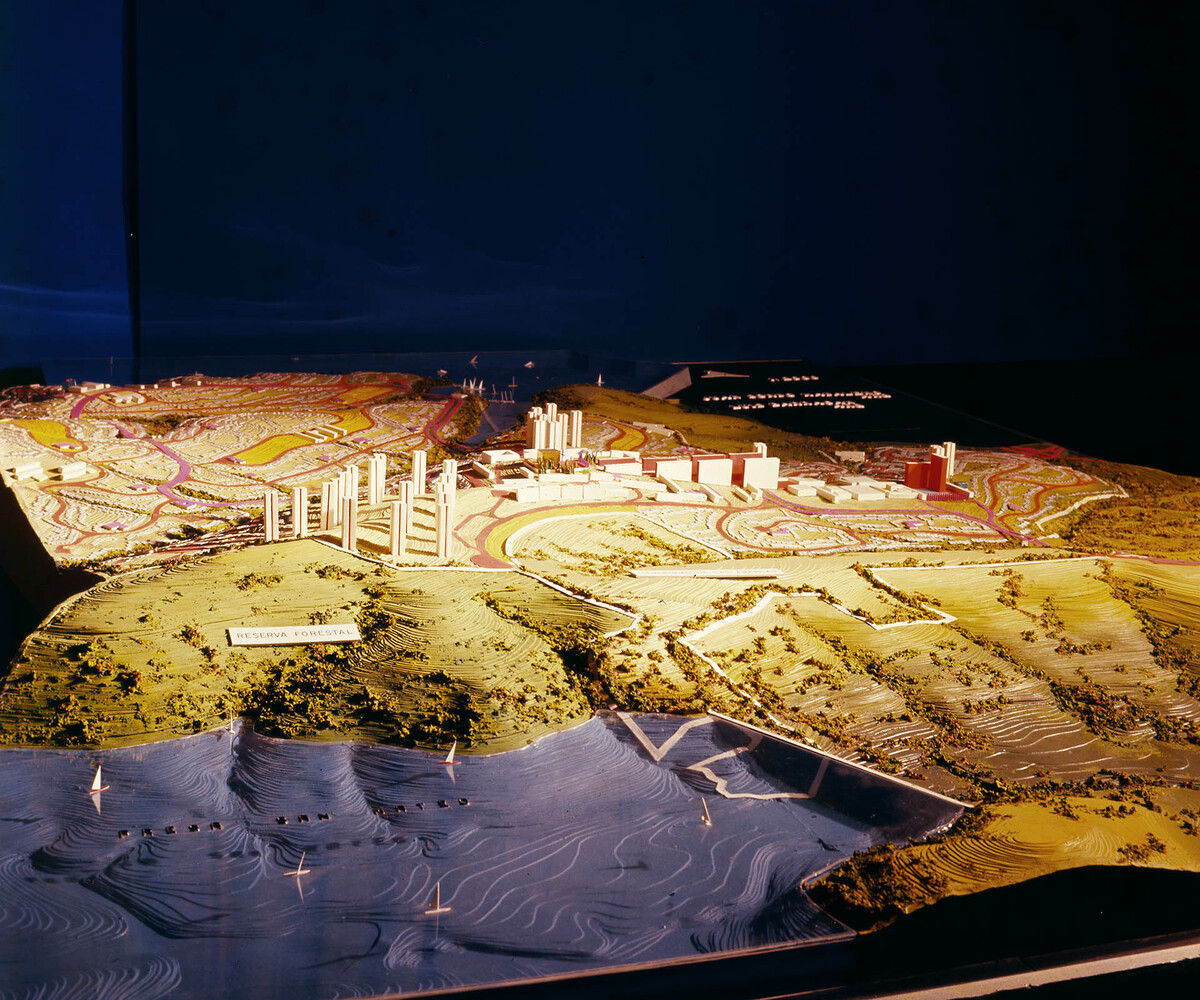

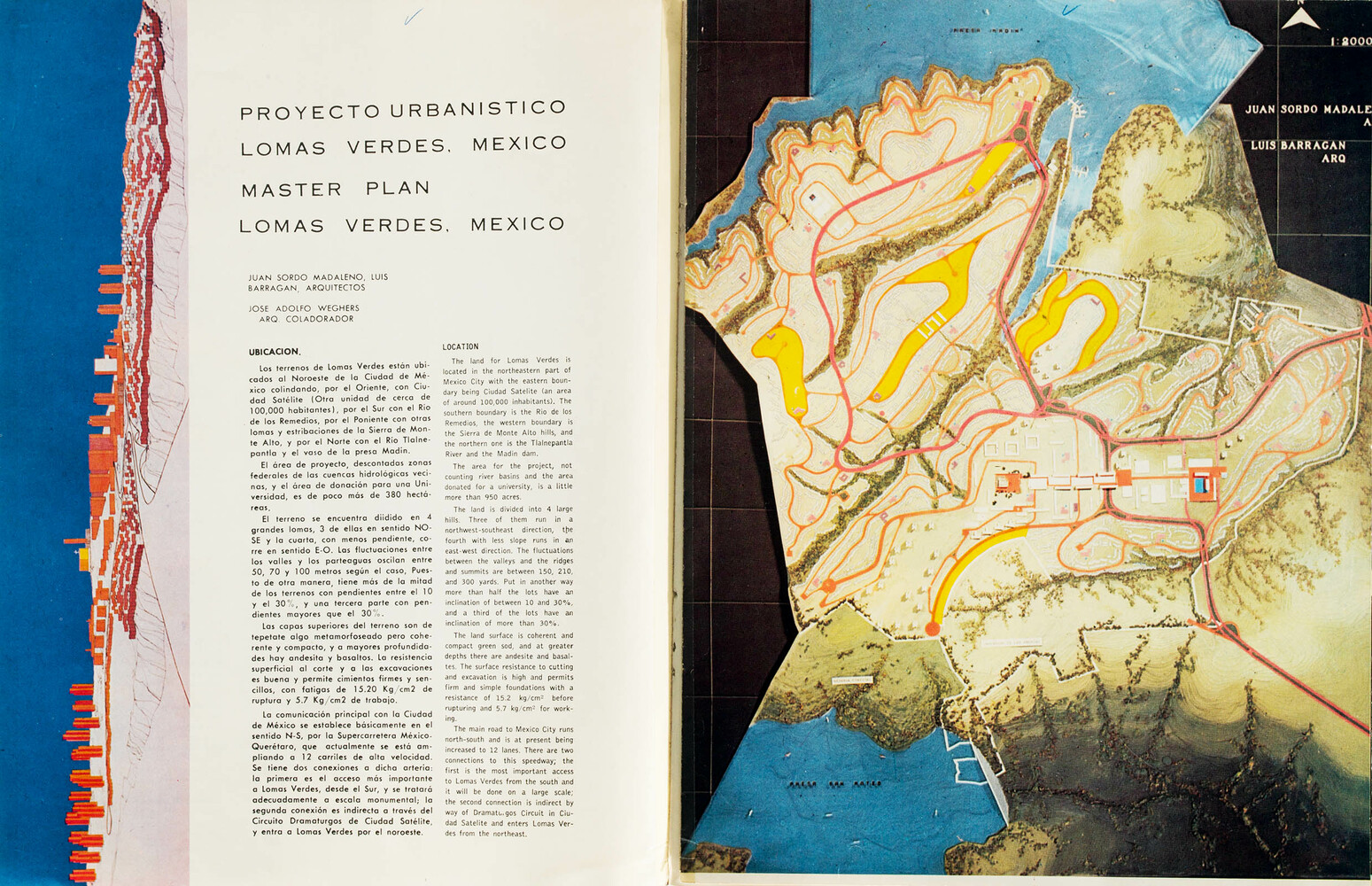

In preparation for the planning of Lomas Verdes, Barragán and Sordo Madaleno embarked on a study trip across Europe in 1964, where they visited some of the most advanced examples of contemporary urban and residential design. Upon their return to Mexico, they commenced work on a project that would occupy them for nearly two years. Lomas Verdes was conceived as an autonomous urban aggregation, connected by a transport network to the nearby capital city. The documentation preserved in the Barragán Archive outlines two master plan options. The first was drafted around 1965 and defines the principal components: a central civic district of monumental proportions, suburbs with housing, road infrastructure and public green spaces. These elements remained consistent with the final version of the master plan, delivered in 1967. The latter presents the same key features, including a linear park system, a similar road network and a civic centre of comparable programme and size that would also accommodate government offices. The final master plan, however, introduces a formal differentiation between the urban nucleus and the suburbs, which are designed and positioned according to the morphology of the terrain, establishing a unique sense of place and resulting in a harmonious integration of built and unbuilt spaces.

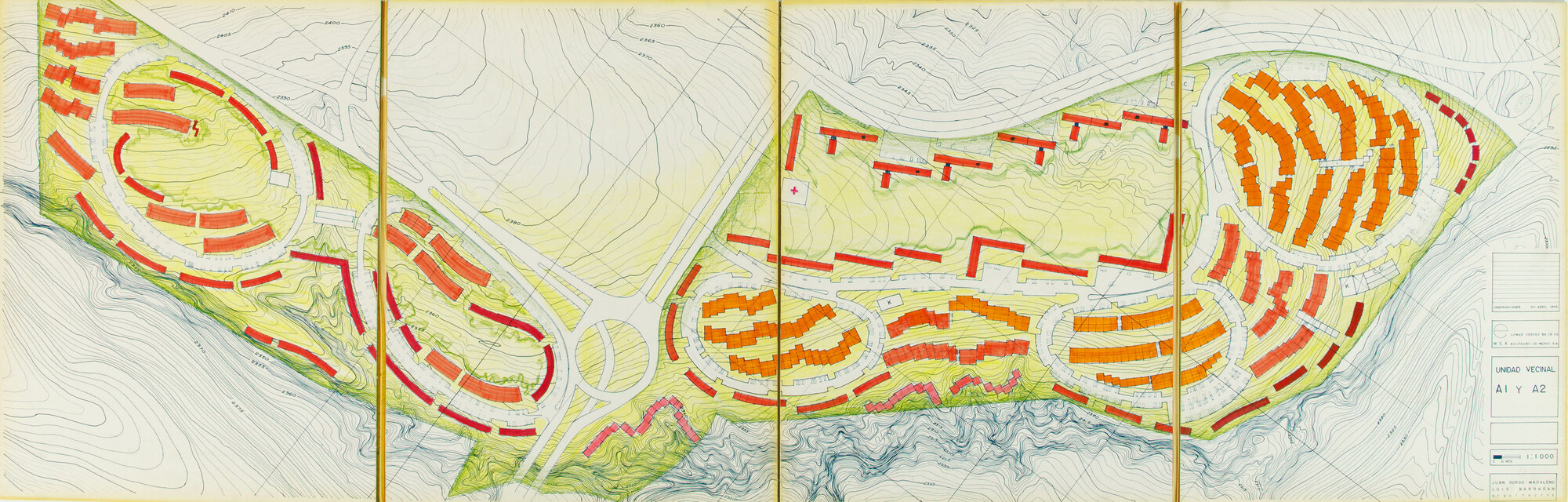

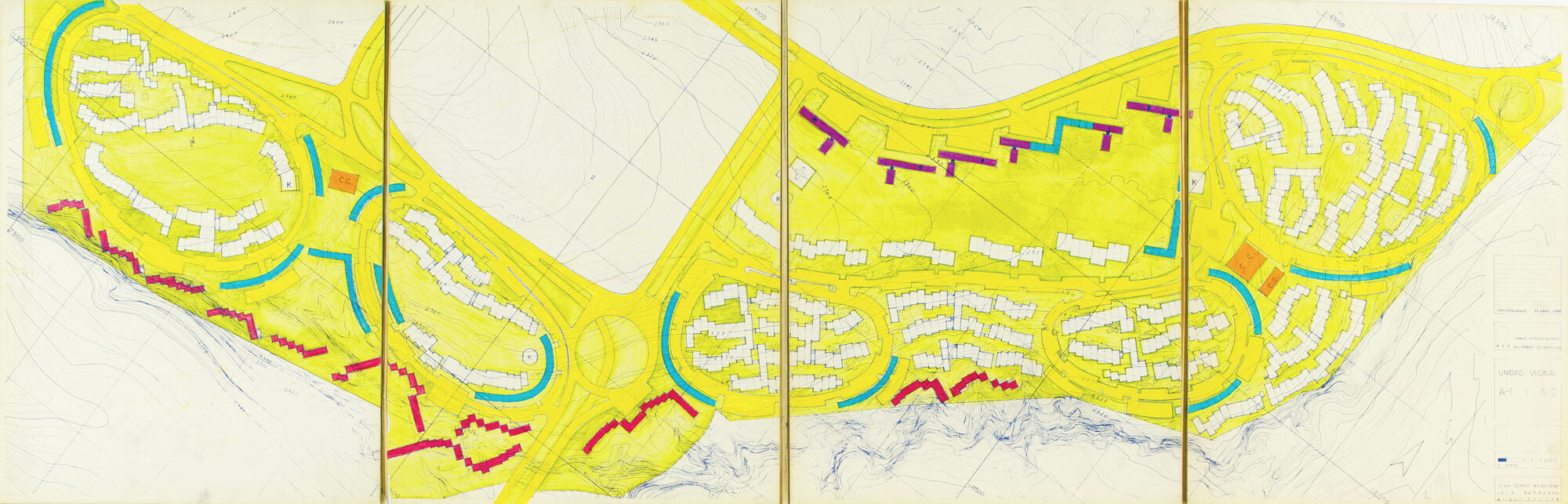

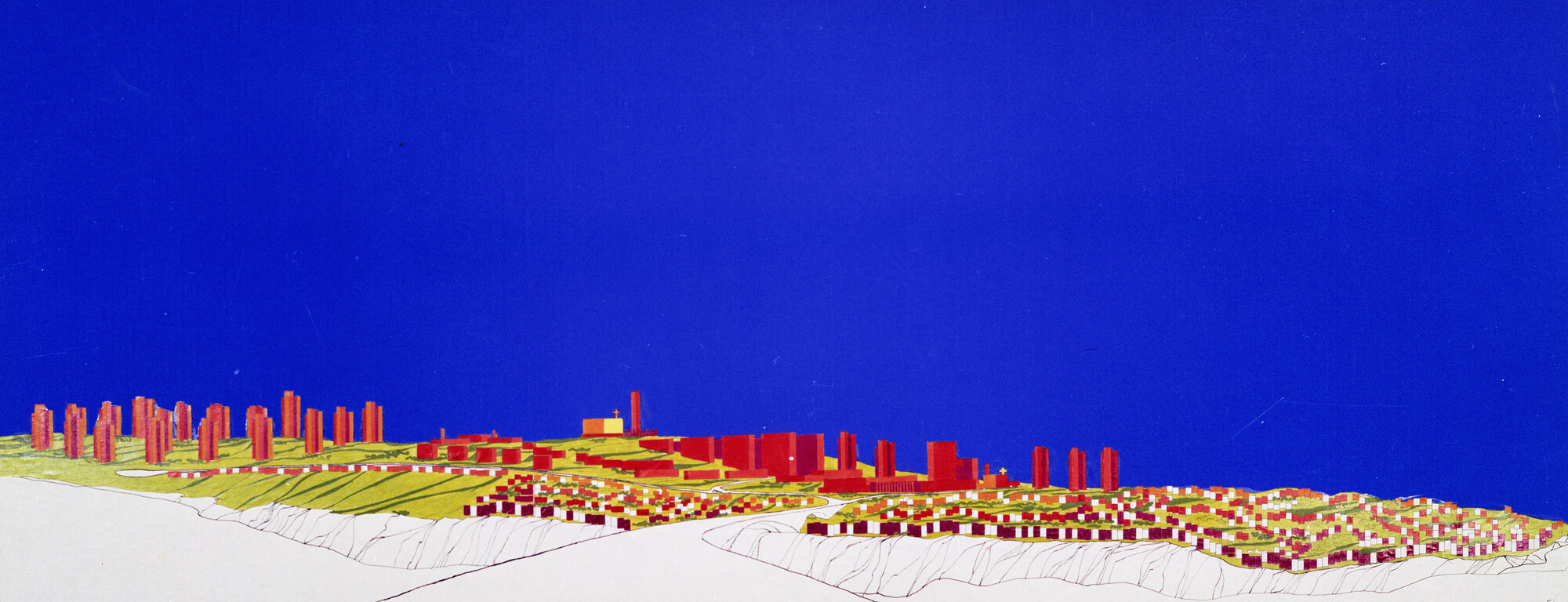

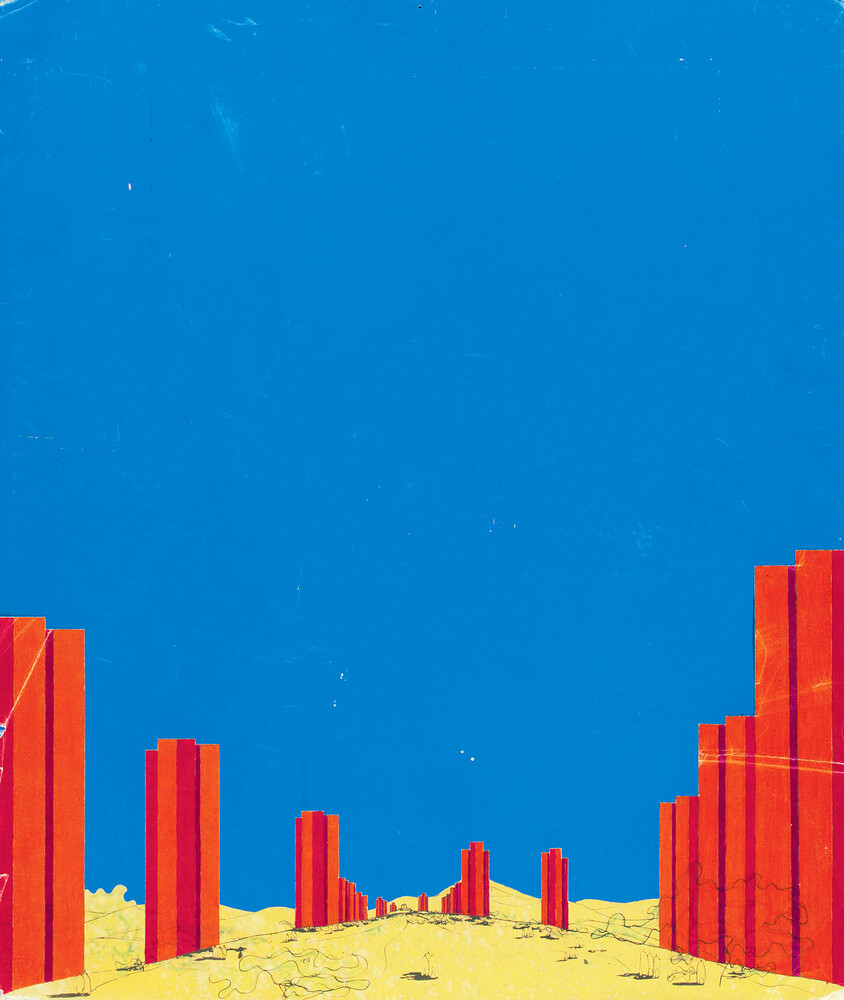

The core of the entire urban structure is a civic zone that the architects called the “Heart of the City”, a direct reference to the theme of the eighth International Congresses of Modern Architecture (CIAM 8), held in Hoddesdon, England, in 1951. Along with this theoretical underpinning, the Lomas Verdes design is influenced by European urban planning, particularly the post-war Scandinavian experience. The master plan outlines a hierarchical constellation of satellite centres, arranged around the civic zone located on the Cerro Boludo hill. High-rise residential buildings punctuate the slopes behind it. Four suburban districts are organized in curvilinear patterns that follow the shape of the hills. Planned for a population of approximately 23,000 to be housed in over 4,250 dwellings, these suburban neighbourhoods, called colonias, have their own core, around which the principal facilities – including shopping areas and schools – are arranged. Each district is further divided into four or five clusters, called unidades vecinales, consisting of 900 dwellings for roughly 4,500 inhabitants.

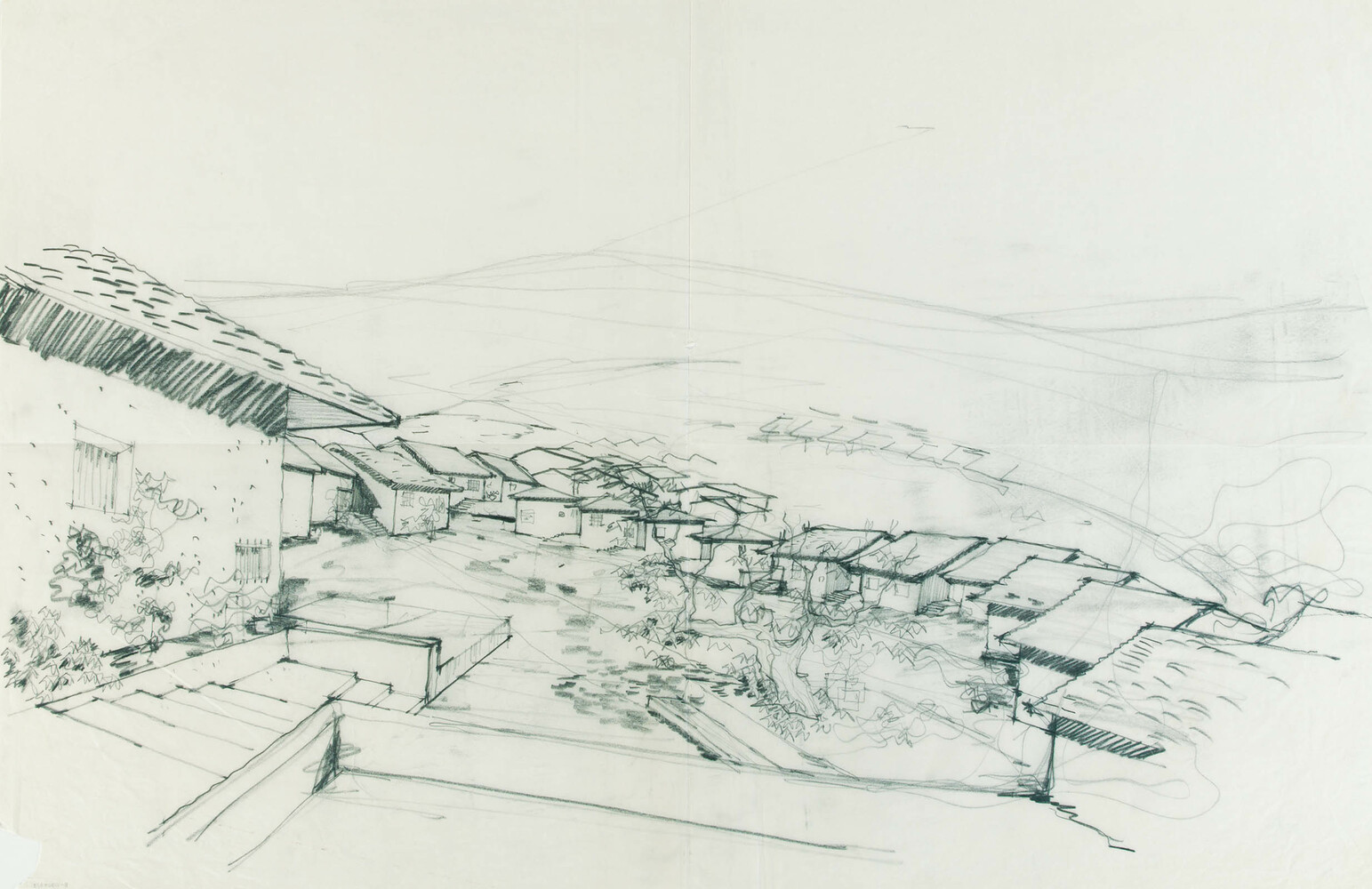

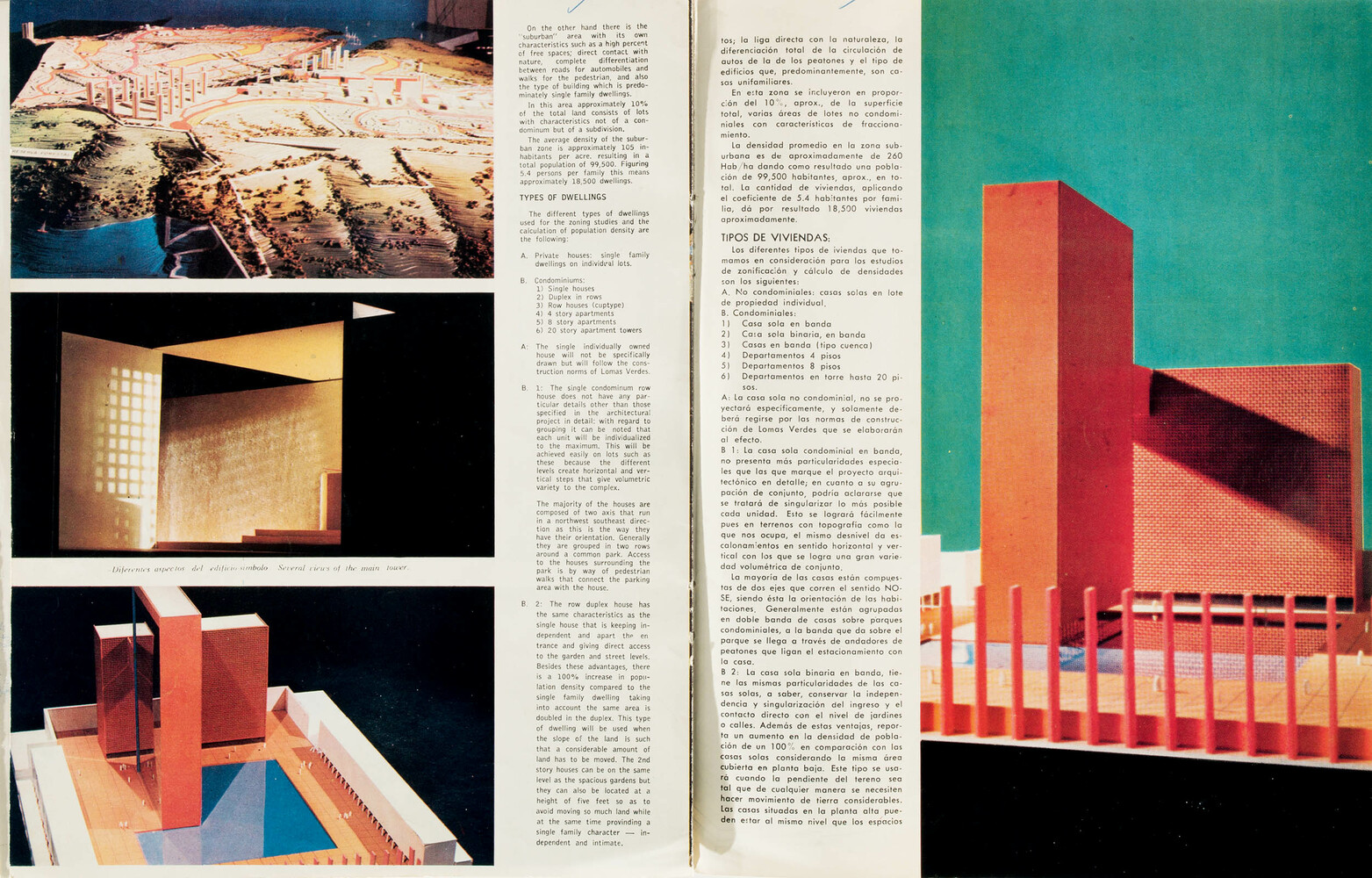

The road system and the green-space network, formed by shared gardens and public parks, constitute the two main infrastructures of the new town. These two realms are arranged without intersecting. In the residential areas, the green spaces and topographical features of the terrain form an organic composition, while the roughly symmetrical layout of the core areas follows a precise geometry across their different scales. Set along the natural lines of the topography, the neighbourhood units present rows of different dwelling typologies: private villas on individual plots, one- and two-family houses, terrace houses, mid-rise apartment blocks (four to eight storeys) and high-rise apartment buildings (up to twenty storeys).

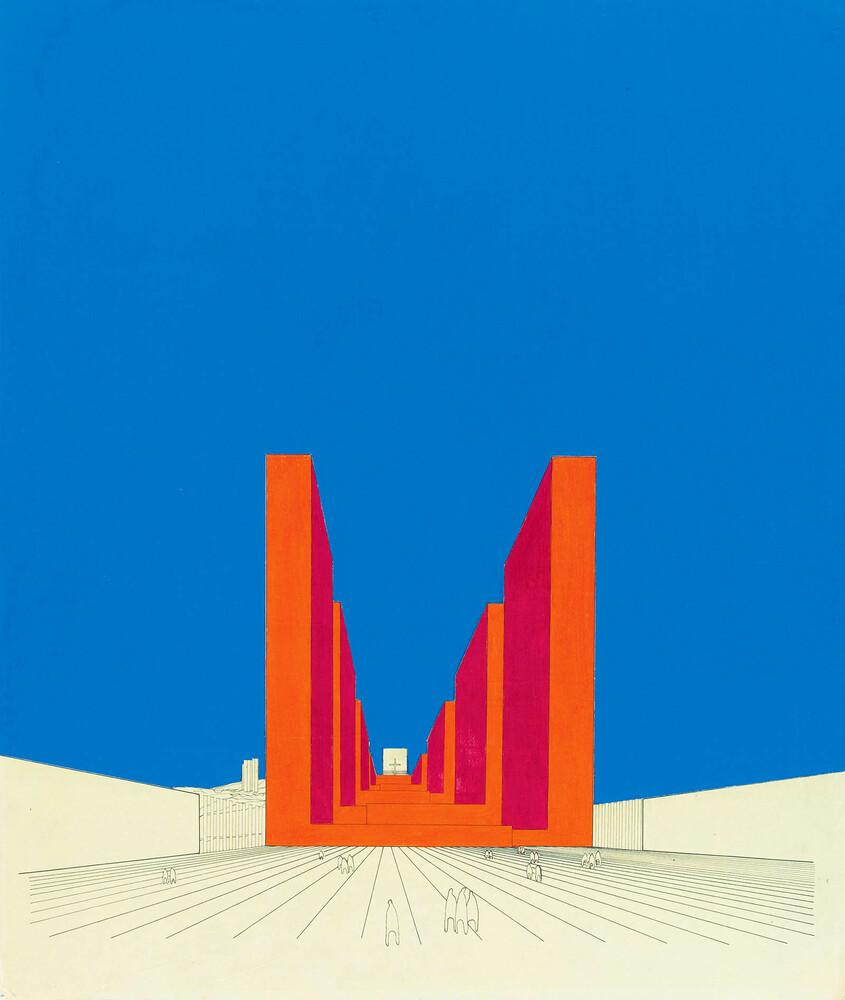

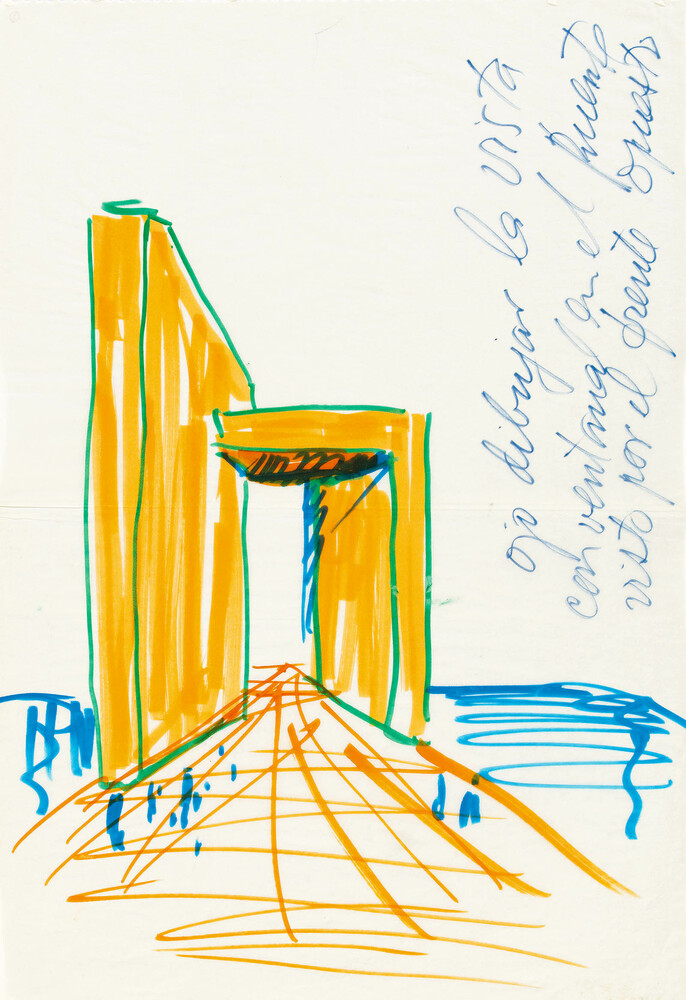

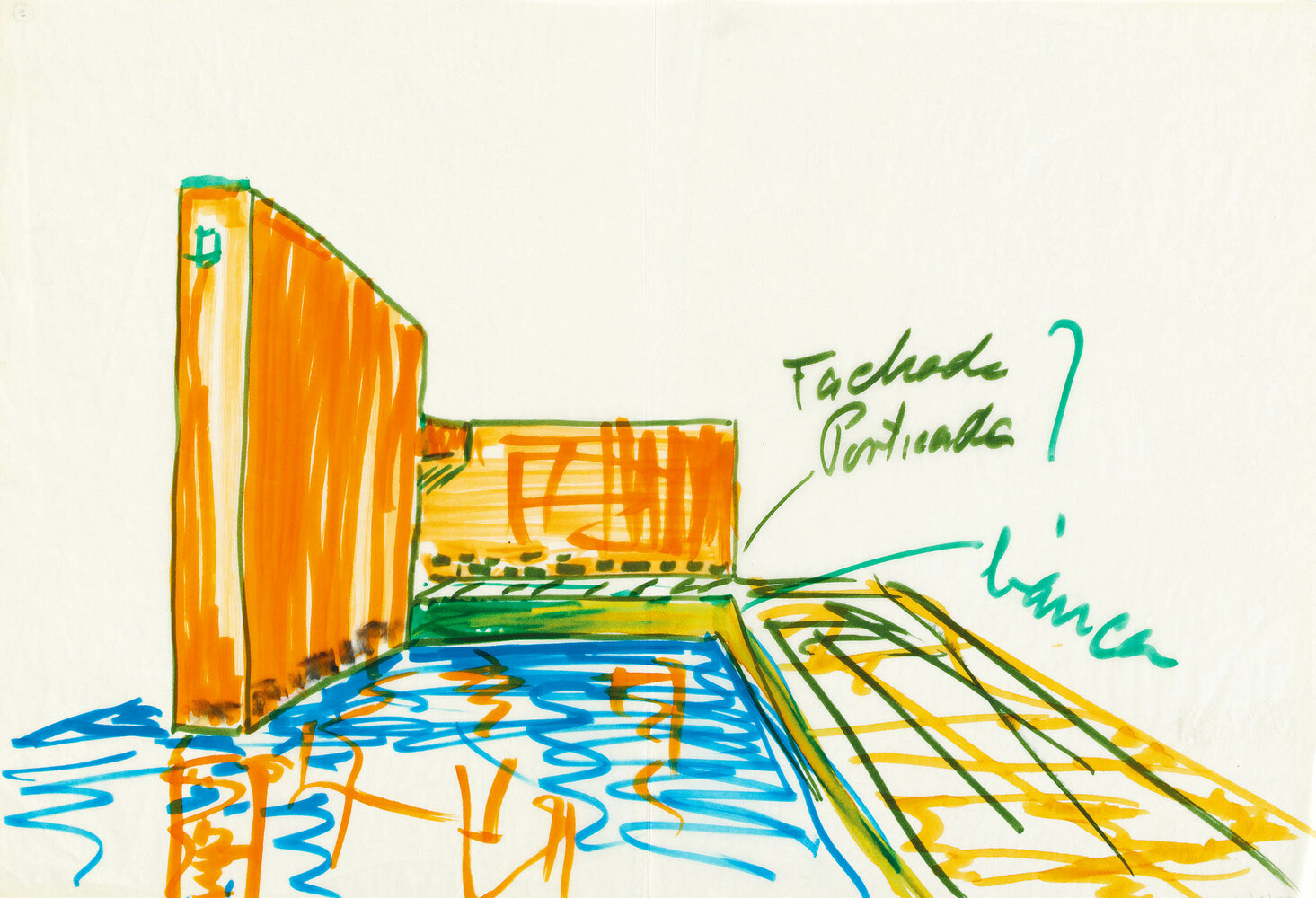

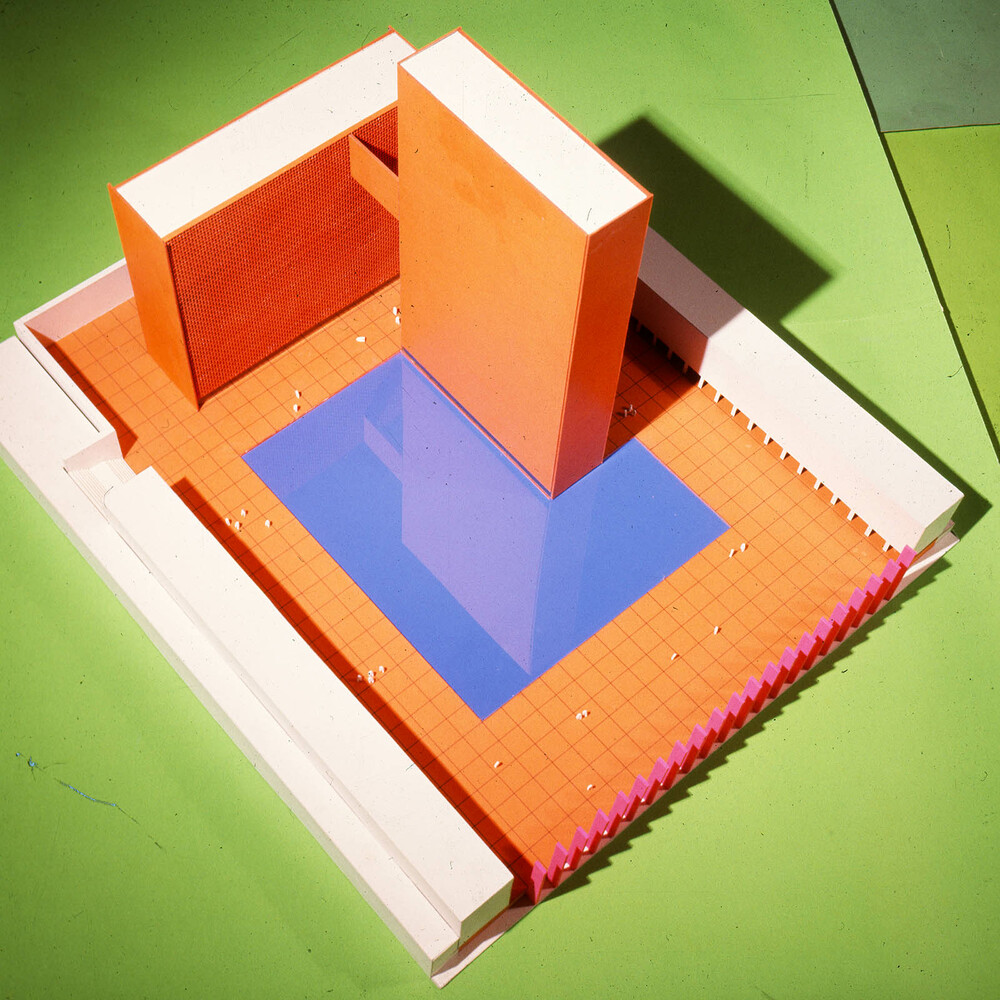

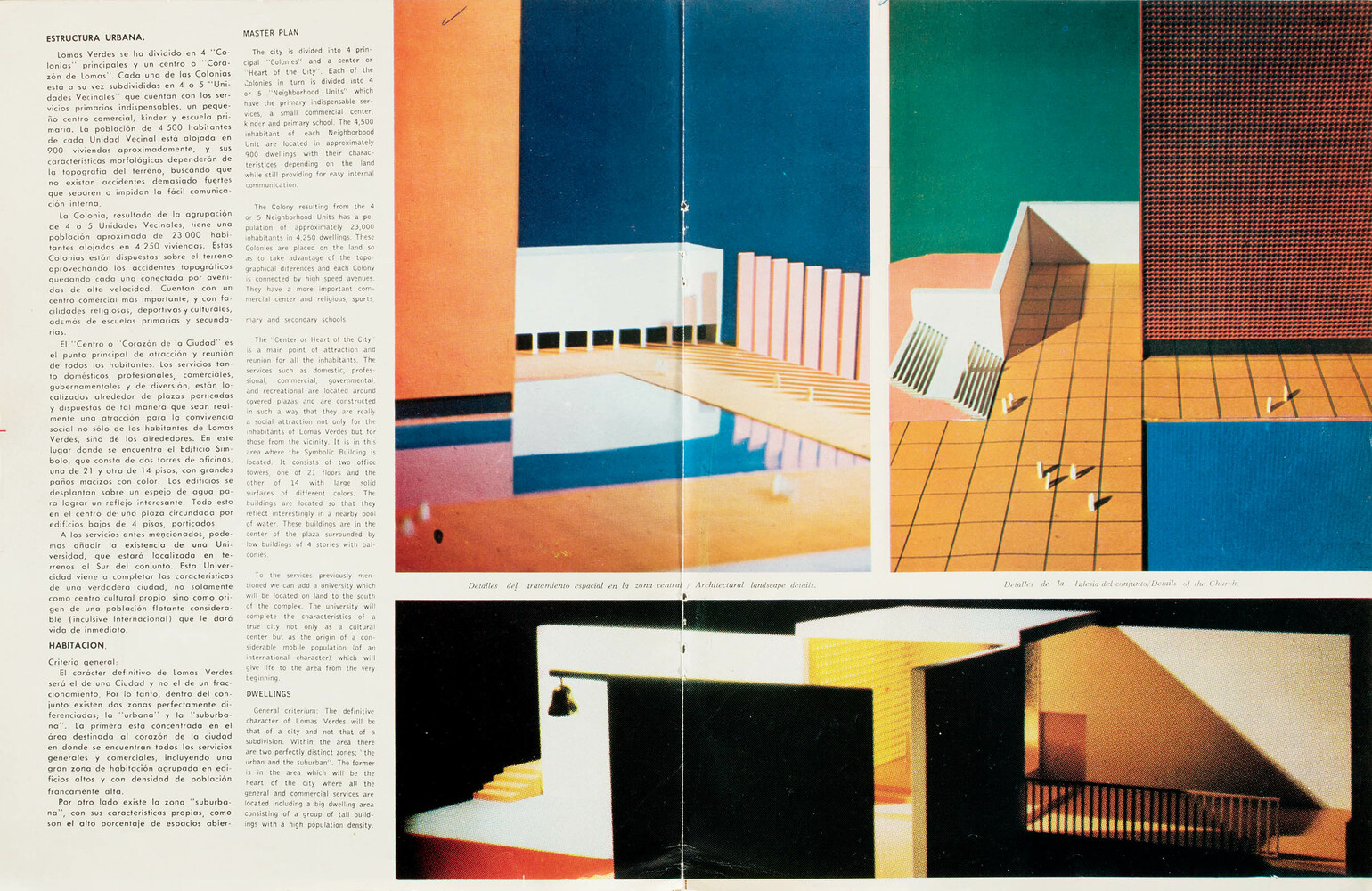

The Heart of the City is both a public urban space and a landmark. Located on the east slope of Cerro Boludo, it is accessed by Avenida Lomas Verdes and Paseo Lomas Verdes, the main thoroughfares that merge in an underground tunnel. The monumental ensemble, painted in a palette of reds, oranges, ochre, sand and white, is configured as a promenade architecturale ascending from east to west. The so-called Ziggurat, a series of stepped terraces flanked by a double row of tall linear buildings, leads to a church at the highest point. On the opposite lower end, a commercial centre surrounds the Edificio Símbolo, a monumental high-rise that dominates the view from the road entering the city. To the southwest of the church, a cluster of seventeen apartment buildings with twenty to twenty-five storeys are arranged along the Cerro del Rayo ridge.

Lomas Verdes was scheduled to be built in eight phases, starting with the Heart of the City and its adjacent residential districts, then gradually expanding westward. The development’s programme encompassed more than 18,400 dwellings spread over an area of 3,800,000 square metres, with 114,000 square metres occupied by roads, 156,000 square metres earmarked for parks, and 290,000 square metres of public space and plazas. In addition, 33,000 square metres were planned for schools and 53,000 square metres set aside for commercial use. In 1968, just one year after the final plan was delivered, Barragán wrote in his curriculum vitae: “This city is under construction; the overpasses and an important avenue have already been built, as well as two of its residential neighbourhoods.” Sordo Madaleno, interviewed the same year, declared: “We will continue with schools, offices, churches, commercial centres and maybe even universities.” Period photographs show the fast-paced progress of the construction work.

The architects’ role became secondary after 1967, when the drawings were entrusted to the technical office of the Lomas Verdes property development company. Barragán continued to contribute sporadically to the project in the role of an advisor. The construction of the road network advanced mostly in line with the plan formalized by the architects, while the residential areas, erected from the 1970s onward, departed substantially from the original design proposals. The focal point of the urban ensemble, the planned Heart of the City, was never built. Consequently, Barragán and Sordo Madaleno’s original vision of suburban and urban living blended in harmony is hard to recognize in today’s sprawling city.