Torres de Satélite is a national landmark consisting of five vertical prisms in concrete, located at the south entrance of Ciudad Satélite, one of the first new towns to be developed outside the administrative boundaries of Mexico City’s Federal District. The monumental work was soon acknowledged as one of Barragán’s major achievements and enjoyed widespread international recognition.

While over the years the towers became one of the iconic features of the capital, the urban environment and the oval traffic island on which they stand changed dramatically, altering their setting and visual effect.

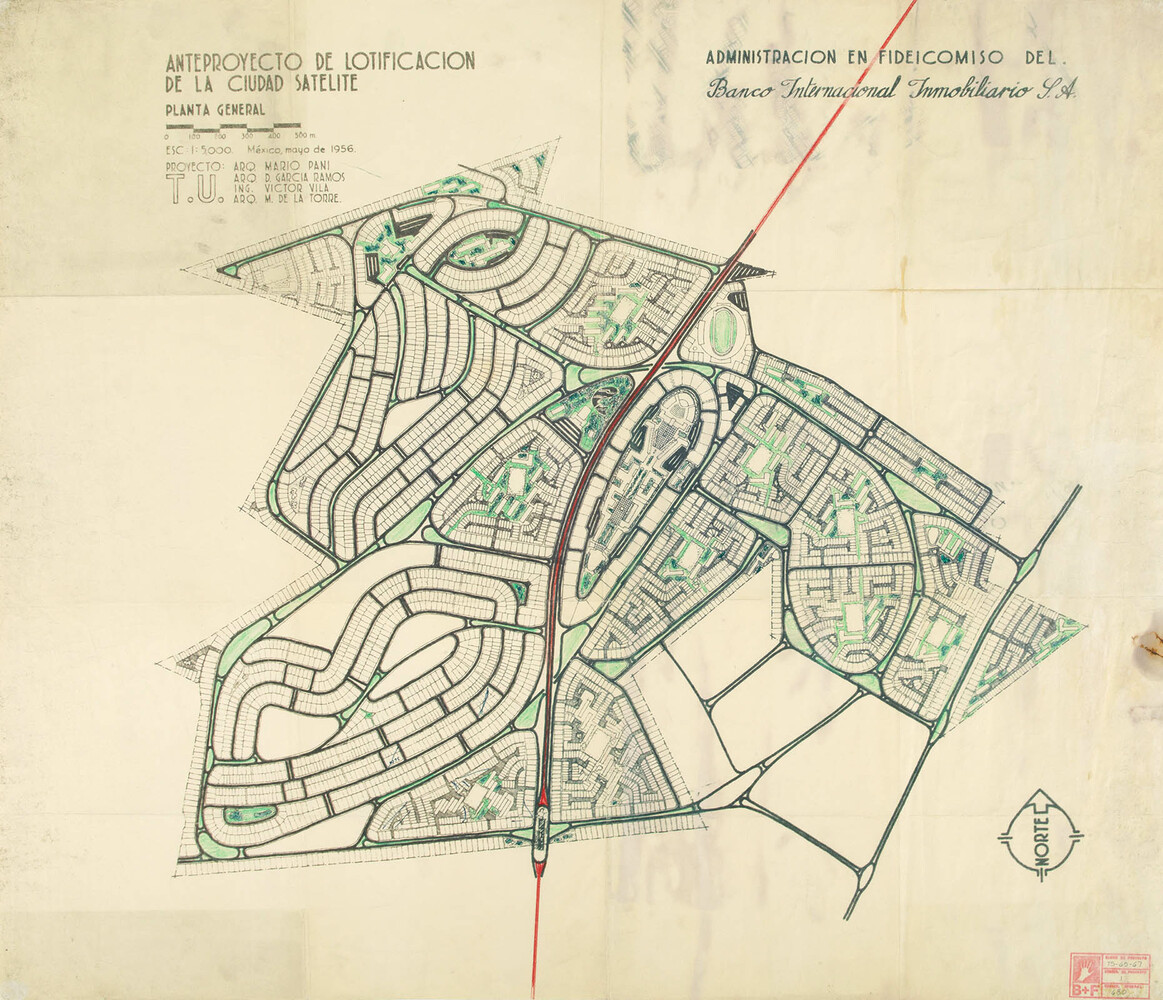

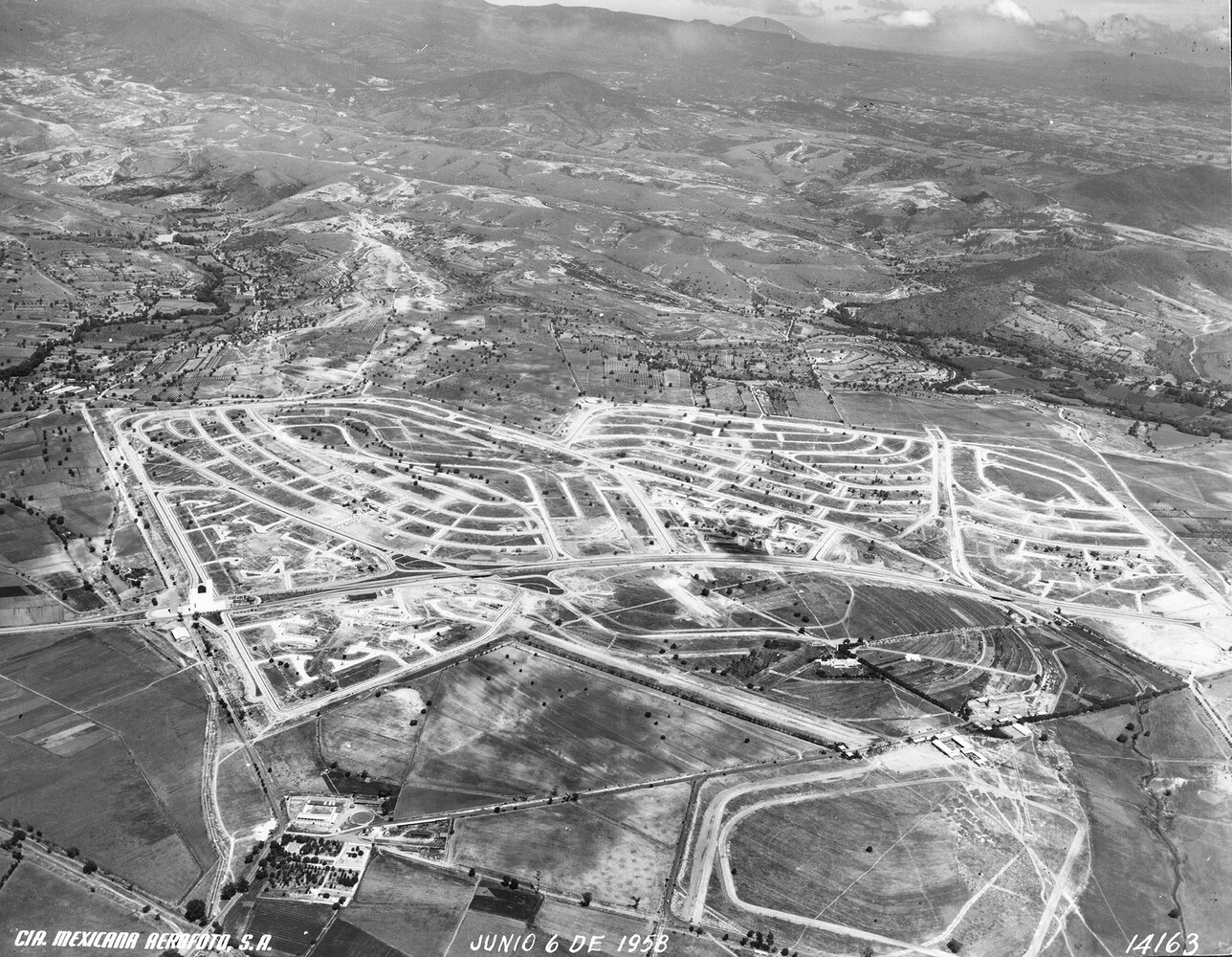

Ciudad Satélite was planned in 1954 by Mario Pani’s office, Taller de Urbanismo, following a new policy preventing further densification of the Federal District of Mexico City. It is accessed via the Mexico City–Querétaro motorway, one of the main arteries exiting the capital towards the northeast. The new settlement was intended for a population of 150,000–200,000 over an area of approximately 800 hectares. It was conceived as an autonomous urban entity with a road infrastructure that would facilitate motorized circulation by avoiding junctions and traffic signals. Pani called on Barragán to contribute to this plan.

The focus of the commission was to create a powerful visual reference point that could be used in the promotional campaign for Ciudad Satélite and would also serve as a highly visible marker from the motorway. Barragán invited the artist Mathias Goeritz, a personal friend of his, to join in the project. The task of producing such a landmark appealed to their shared interest in a new, more abstract form of urban monumentality.

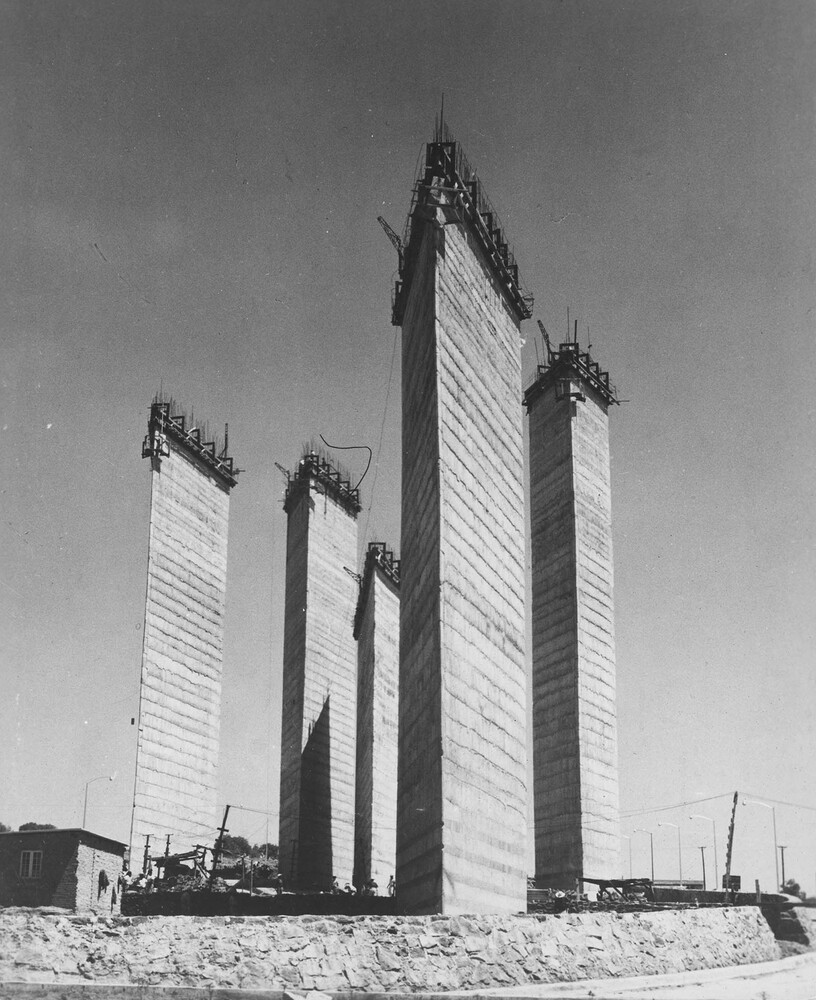

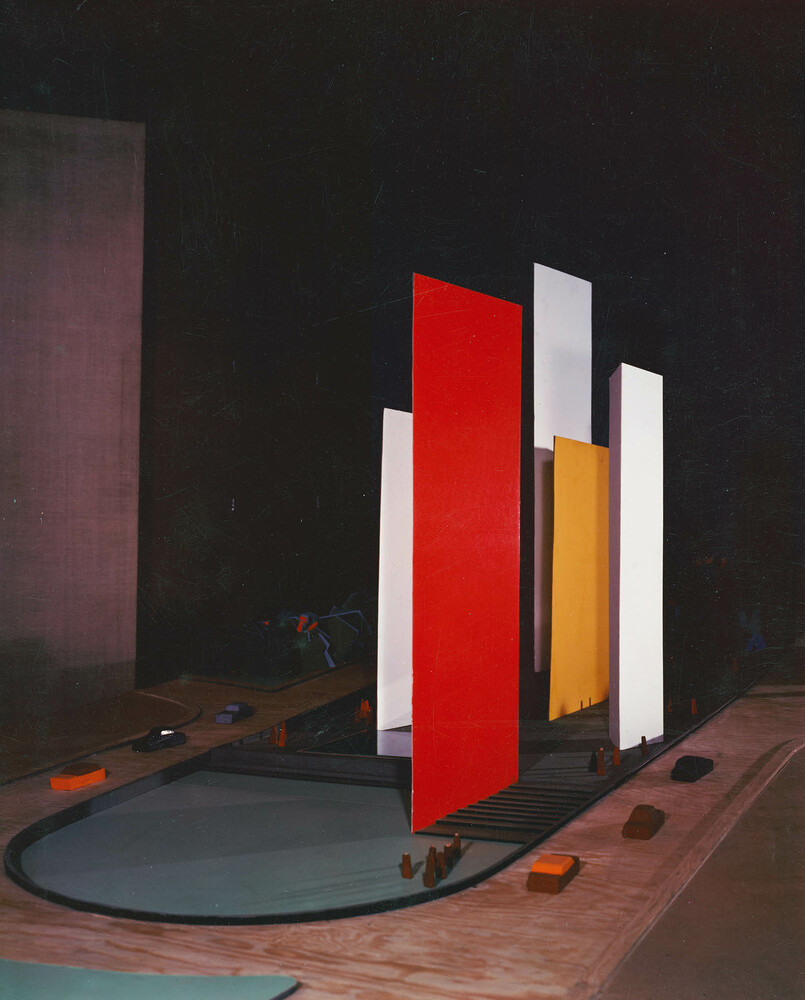

In the first months of 1957, a composition of several vertical volumes was developed. According to statements by both Barragán and Goeritz, the idea was inspired by two archetypal skylines – the Tuscan town of San Gimignano with its medieval tower houses, and the New York borough of Manhattan with its modern skyscrapers. Further work on the preliminary concept led to a final design proposal consisting of five towers in the shape of triangular prisms, rising between approximately thirty-seven and fifty-seven metres. Along with this spatial and volumetric configuration, alternate colour schemes were developed, proceeding from the first conceptual sketches and preliminary renderings to numerous experiments on a three-dimensional model. The chromatic composition that was initially executed in the early months of 1958 contrasted three white towers with one painted in orange and another in yellow. Shortly afterwards, one of the three white prisms was repainted in blue. The landmark was again refurbished in 1967, this time with a palette consisting exclusively of bright orange and yellow hues.

The towers were built in a single phase, prior to the residences and facilities that were soon to occupy the surrounding area. Several aerial photographs taken in late 1957 and June 1958 show the bare prisms cast in concrete, standing tall in an elongated traffic island at the centre of the freeway, amidst a landscape of outlined roads and empty plots.

One of the effects pursued by Barragán and Goeritz in the design and configuration of the ensemble involves the dynamics of how it is perceived. For those travelling from the south, leaving the capital behind and driving up the motorway, the towers appear as sharp blades, with their pointed edges increasingly accentuated upon approach. In contrast, as one proceeds alongside the traffic island, they transform into flat rectangular planes of unexpectedly imposing proportions. To those approaching the city from the north, the prisms stand out against the urban landscape like a dense composition of slender, tall towers. All these contrasting visual impressions dwell in the mind of the viewer, conjuring up a multifaceted image of the landmark, one with a distinctly urban character, uncanny and familiar at the same time.

In the spring of 1968, a controversy arose between Barragán and Goeritz over the project’s authorship, partly driven by its wide international exposure as a campaign image to promote the Mexico City Olympic Games. After a number of publications omitted or marginalized Barragán’s role, he wrote a memorandum reconstructing in detail the evolution of the design process and his contribution to the joint concept. Once made public, the issue escalated in a flurry of articles and press interviews, with Barragán and Goeritz persisting in their opposing positions and ultimately sacrificing the personal friendship and professional partnership that had proven so fruitful for both. The bitter dispute was resolved many years later, in August 1987, thanks to the mediation of their mutual friend Ignacio Díaz Morales, who asked Barragán and Goeritz to sign a document attesting to the work’s shared authorship. Irrespective of the dispute, what remains is an austere and powerful landmark of singular impact and fascination, well advanced for the time of its conception and construction, a unique fusion of art and architecture.