Barragán’s Capuchin Convent Chapel is indisputably recognized as one of his seminal architectural works. Its prolonged genesis reflects a meticulous attention to detail and a slow process of refinement that unfolded over more than six years.

Late in the summer of 1954, Barragán offered his professional services and some financial support for the construction of a chapel to the monastic order of the Clarisas Capuchinas Sacramentarias del Purísimo Corazón de María. This religious community still has its home in Tlalpan, a village south of Mexico City that was eventually absorbed into the urban sprawl. The commission, which included the refurbishment and extension of an existing building, appealed to the architect’s religious beliefs as well as his profound interest in ecclesiastical architecture and religious art. The convent complex was developed in several phases: the reorganization of the existing colonial building and its annexes, the construction of a new chapel and an extension towards the rear of the plot.

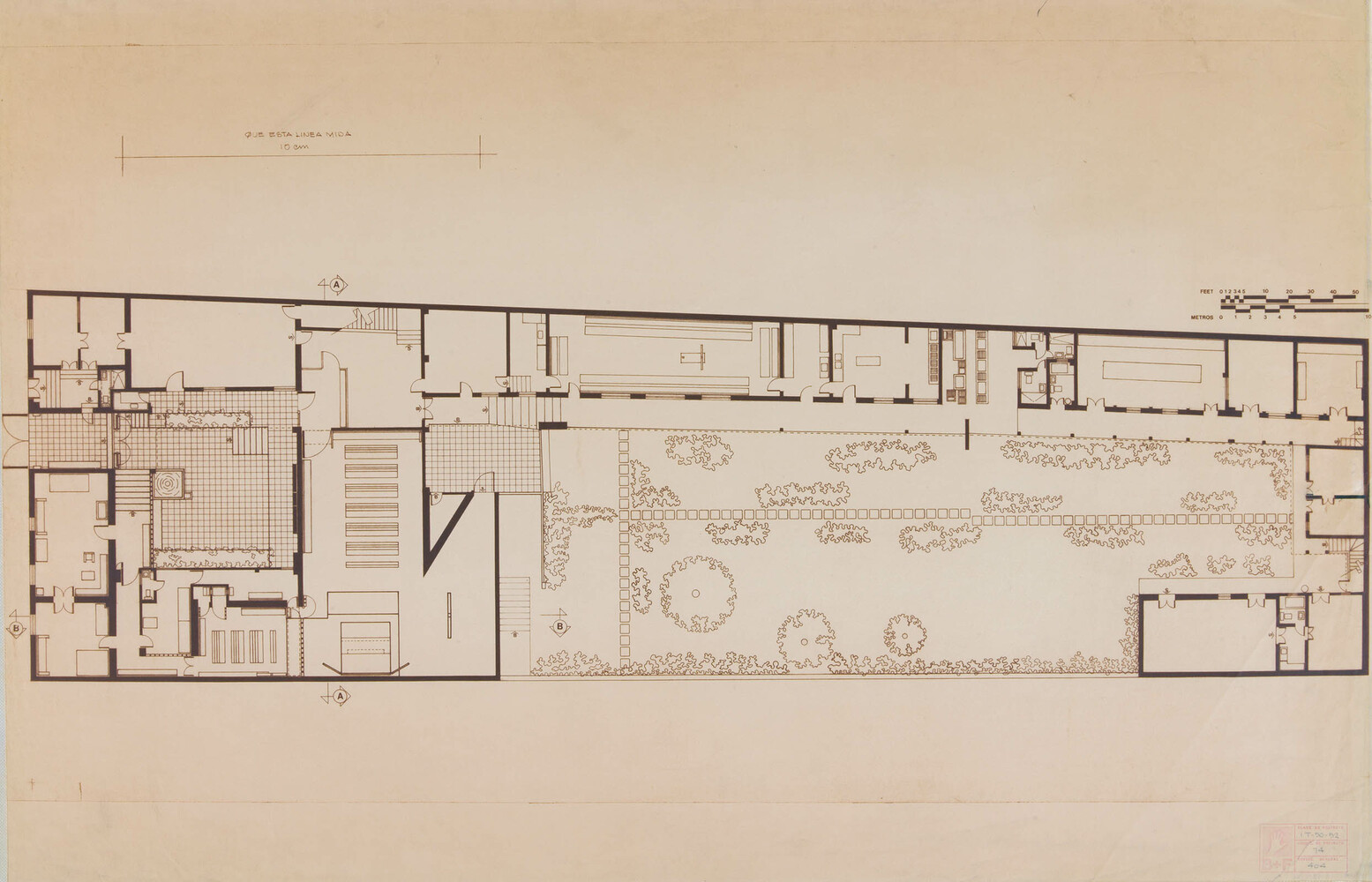

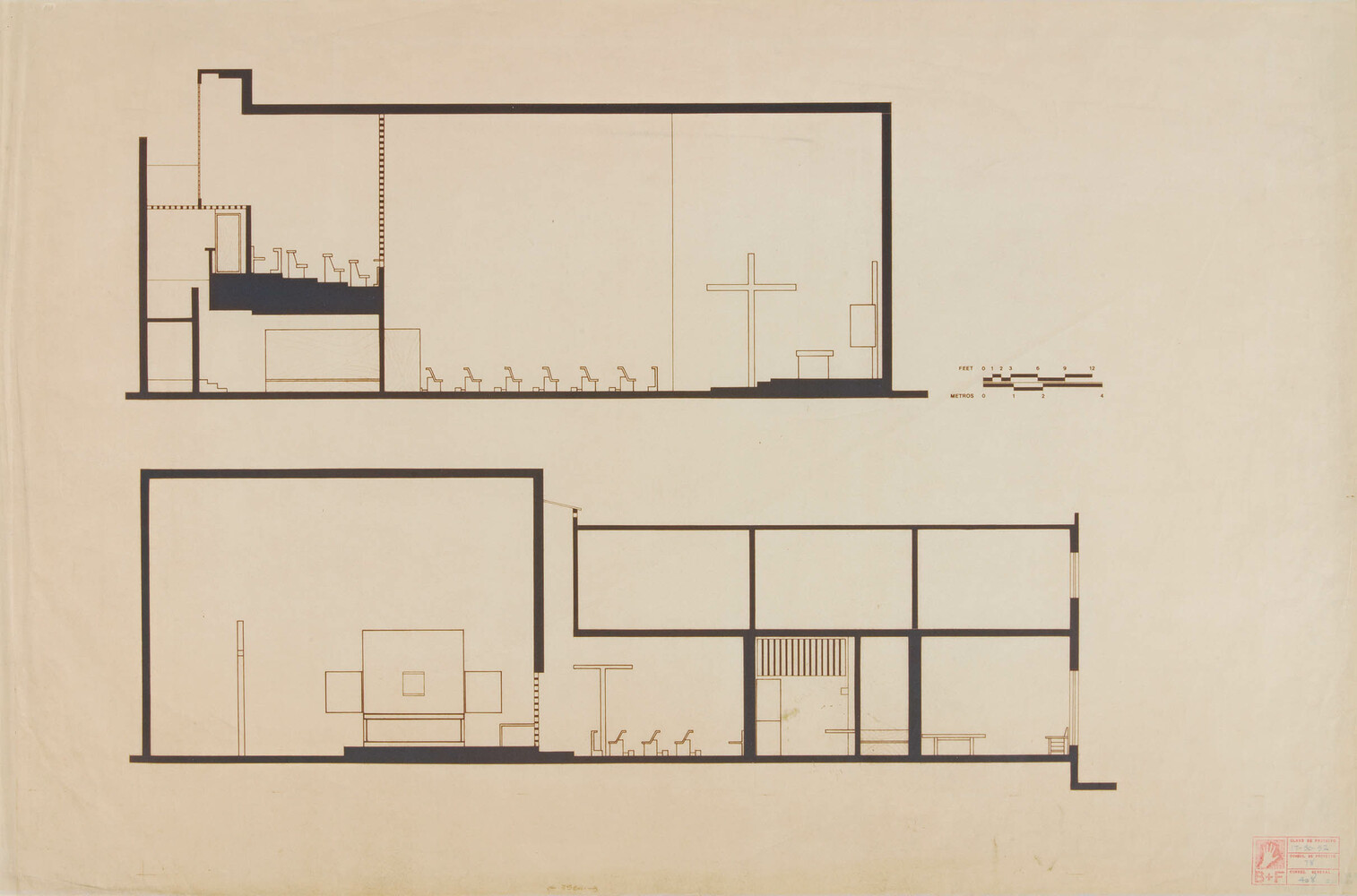

The existing structure of a former colonial house stood at the front of an elongated plot measuring twenty-seven by ninety metres. The first proposal combined two longitudinal wings along the lateral boundaries with the transversal volumes of the planned chapel and refectory, thereby defining two inner gardens. A vegetable patch was to occupy the southern side of the plot. Barragán continued to modify the chapel’s orientation by changing entrance points and circulation patterns, while also transforming the gardens into paved patios. The rectangular nave of the chapel was expanded with the addition of a lateral space, partially screened by a protruding wall. In later iterations of the plan, this wall evolved into a simple yet sophisticated visual device, the so-called quilla (keel). Consisting of a prismatic triangular volume formed by two walls joined at an acute angle, the keel splayed the formerly rectangular footprint of the adjoining space, thus contributing to a dynamic visual composition in which both the lateral and main naves converge towards the altar.

Barragán continued to make refinements and adjustments to the design during the construction process. The chapel was consecrated on Sunday, 24 April 1960. Further details and features were implemented over the next several years, probably reaching completion around 1963. For this work, Barragán relied on the advice of the artists Jesús “Chucho” Reyes, with whom he shared a keen interest in religious art, and Mathias Goeritz, who contributed some key elements of the chapel interior, notably the full-height stained glass window in the lateral space.

The massive reredos, a wooden triptych fixed to the back wall behind the altar, is the focus of the liturgical space. Covered with gold leaf, it reflects the light from the window of the choir. The altar is a monolithic, rectangular prism of concrete, with a frontal wood panel also covered in gold leaf. Its position was pushed forward towards the congregation in accordance with the new liturgical directives of the Second Vatican Council. The luminous reflected light produced by the yellow-stained glass of the lateral window intensifies the orange hue of the surrounding walls. This ethereal atmosphere underscores the mystical symbolism of a freestanding cross positioned between the presbytery and the lateral space. Painted the same orange as the walls, the cross appears dematerialized, its subtle presence revealed only by the incident light.

The flooring, pews and confessionals, as well as the windows and doors, are made of varnished pine planks. All of the furnishings, simple and clearly inspired by the principle of Franciscan austerity, were designed by Barragán and manufactured by his master carpenter.

Leading to the chapel is a patio paved in lava stone. The tall exterior wall of the chapel, plastered in white lime, bears the relief of a full-height cross. Opposite, set against a yellow lattice wall, is a cuboid fountain made of concrete and painted black. Filled to the brim with overflowing water, it mirrors the lattice and the bright colour of a bougainvillea growing across the side wall.

The community areas of the convent are sited towards the back of the plot. They include the kitchen and refectory on the ground floor. The upper level, featuring a continuous access balcony, was originally occupied by the dormitories and later transformed into work spaces.

Barragán’s unusual status in this project as both architect and benefactor gave him the freedom to influence many aspects of the environment. In addition to conceiving the furnishings and selecting the tableware, he also designed the simple altar cloths in coarse linen and the chasubles and capes in woollen fabric. This project can be seen as a Gesamtkunstwerk, an all-encompassing and aesthetically consistent vision of contemporary religious architecture.

The completion of this project fulfilled Barragán’s quest for a harmonious integration of the visual arts. To this day, the transcendent nature of the Capuchin Convent Chapel is palpable, preserved by the nuns who have dwindled in number over the years but continue to watch over this work of faith and architecture.